The Laws That Changed The Sales Profession

There aren’t too many professions that have required the government to step in more than the sales profession. It’s a profession that seemingly has always sought to push the boundaries to the point where some official body has had to jump in and say, “Ok, here’s how you’re allowed to do this.”

While we so often think that “technology” or “information availability” has created the largest shifts in the world of selling, it turns out legislation has caused more considerable shifts than either one.

Much of how we sell has been shaped by laws designed to protect fair trade, pricing, consumers, and, more recently, outreach. Would you like to learn more about those situations and relevant legislation? Let’s go through them.

—–

Let’s go back to the 1860s. The Civil War had ended, the Industrial Revolution had arrived, and the economy was exploding. You had railroads stretching from coast to coast, oil and steel production exploding, while the banking industry was consolidating around a few powerful families.

These companies got greedy, and in many cases, realized they could all make more money by joining forces rather than competing with one another. They formed “trusts”. So, imagine the core steel businesses getting together, realizing the only way to get steel was from one of them. So, they would agree on a floor by which prices would be set. Customers had no alternatives except through one of them.

Or railroads getting together and all charging high rates. In some cases, they just carved up the country – “you take the Midwest, we’ll take the northeast”, etc., so they weren’t competing against each other.

John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil would come in and slash oil prices in a local market until the competitors went bankrupt, then raise the price way up once they had a monopoly on that market.

In some cases, the trusts would just buy out the smaller competitors and fold them in, so that before long, competition disappeared.

By the 1880s, small businesses, and even more so farmers, would be outraged. The railroads were gouging the farmers’ freight rates. The small businesses couldn’t possibly compete with the massive organizations that were getting preferential pricing. And workers were getting sweatshop-level pay while the tycoons (like Rockefeller, Carnegie, J.P. Morgan, and Vanderbilt) acquired unbelievable amounts of wealth.

Along came the first significant piece of legislation that affected the sales profession:

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890

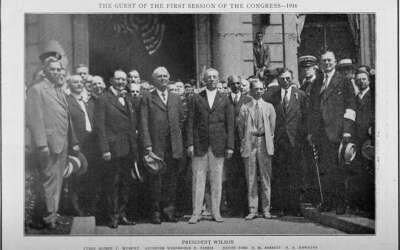

Senator John Sherman

Named after Senator John Sherman, the law was established to (a) make illegal any “contract, combination, or conspiracy in restraint of trade” and (b) Any attempt to “monopolize” or conspire to monopolize a market. It was written in a broad way so that courts could apply it in many untilthen not even imagined ways.

Before the Sherman Act, salespeople didn’t really have to sell, the businesses themselves controlled. Buyers had no alternatives. The Sherman Act opened the door to competition to not only survive, but compete. The concept of actually “differentiating” in sales was born.

In a way, the Sherman Act kicked off the modern concept of sales.

Just like how salespeople game their compensation plans, the industry gamed the Sherman Act. It was great theoretically, but because of the broadness by which it was written, it left massive holes, ones in which business leaders and lawyers figured out how to get around it. In some cases, companies flaunted the lack of teeth of the Sherman Act. In the October 20th, 1892 edition of “The NCR”, which was the newsletter sent to all of their salespeople, the edition’s first paragraph reads, “We have a monopoly. We propose to keep it. The government has given it to us through our patents. All the requirements ask of the Salesmen are energy, ability, and honesty.”

First, the language was so broad that courts tended to side with the businesses, given the language did not have much meat.

Second, while Sherman banned these trusts from forming and fixing prices, it didn’t stop companies from giving special deals to squeeze out the small competitors in local markets.

Third, Sherman didn’t forbid companies from merging. In the early 1900s, there were huge consolidations in steel, tobacco, meatpacking, and banking. Owning 90% of the market wasn’t a monopoly, according to the law.

Fourth, there were problems being created by companies that were outside of the scope of monopolistic practices.

And fifth, the Sherman Act actually crushed unions…because, when a union went on strike, that was considered a “restraint of trade”, so the monopolists continued to thrive while the unions suffered.

While Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Taft tried to use it to break up the giants to make selling easier and more accessible, they kept growing.

The Clayton Act of 1914

It wasn’t until 1914 that the Clayton Act was enacted to spell things out.

– Price discrimination that lessened competition was banned

– No more exclusive contracts that forced loyalty

– …along with a number of other details that specifically gave salespeople and buyers a freer, fairer marketplace.

Selling, especially in those industries, lent itself to lawyers writing contracts to game The Sherman Act. But now, you won because your alignment to customer outcomes was better. Salespeople really needed to sharpen their skills, so The Clayton Act had a significant impact on the future of the sales profession.

December 1st, 1914 Cover of Public Service Regulation and Federal Trade Report, with a handwritten letter discussing the FTC Act, Clayton Act, and Sherman Act

In the same year, along with the Clayton Act, came another significant shift that profoundly impacted the sales profession. If you’ve ever heard the phrase “unfair or deceptive practices”, the FTC was there to squash them.

While Sherman and Clayton were about managing the competitive landscape, the FTC was all about truth in selling!

Until 1914, the idea of “Patent Medicines”, also known as “snake oil” was still a thing. Salespeople traveling around as well as newspaper advertisements promising miracle cures for everything from baldness to tuberculosis to, well, everything. Up until then, many of these snake oils contained things like alcohol, cocaine, or even opium. Remember, the original Coca-Cola formula had cocaine in it. These types of salespeople and advertisements caused addiction problems, too.

Testimonials were largely fake, and there were no ramifications for publishing them. Even doctor testimonials didn’t have to come from actual doctors. Imagine that type of thing today…just totally making up case studies and endorsements. One of the more amazing stories I read was about a popular asthma cure that was advertised nationwide was really the smoke of burning paper. Inhale it as a cure.

There were no regulations regarding ingredients in the things you purchased. Although the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 required labeling, telling the truth in said labeling wasn’t yet a thing. Bait-and-switch selling was also popular at the time. Use a low-priced item to get someone interested, then tell the customer it’s all sold out, but a more expensive version is available.

The FTC’s establishment put an end to all of that – to protect buyers from lies. And along with it, it also meant that salespeople couldn’t just say anything to close a sale. Your claims must be backed by the truth. We were now full bore in an era of sales based on trust and credibility, versus through deception.

The Robinson-Patman Act of 1936

By the 1930s, the U.S. economy was deep in the Great Depression. People were struggling, small businesses were barely hanging on, and yet the big chain stores like A&P, Woolworth’s, and Sears were thriving.

Because of their massive buying power, these chain stores could walk into a manufacturer’s office and say, ‘Give us a better price, or we’ll take our business elsewhere.’ And the manufacturers, desperate to move product in a weak economy, gave in. They sold to the big chains at prices that were 10, 20, sometimes even 30% lower than what they charged small local grocers or shopkeepers.

Now imagine you’re that small-town grocer. You’re buying canned goods from a wholesaler at, say, $.15 a can. The A&P down the street is paying only $.10 a can, and then turning around and selling them to customers for $.12. That’s cheaper than you can even buy them for. There’s no way you can compete, and your customers, who are just as strapped for cash as you are, leave your store for the chain.

This wasn’t just happening in groceries. It was playing out across retail; in clothing, hardware, dry goods, you name it. And the cries of unfairness were getting louder. Small businesses argued that if this kept up, they’d all be wiped out, and America would be left with nothing but giant retailers.

That’s where the Robinson-Patman Act of 1936 comes in. Sometimes called the ‘Anti-Chain Store Act,’ it was designed to stop this kind of price discrimination. In plain language, it said: if you’re a manufacturer, you can’t sell the same product to two different buyers at two different prices if it hurts competition. And you can’t give the big guys extra perks, like advertising allowances, display money, or free goods, unless those same opportunities are offered to the little guys, too.

For the sales profession, it forced pricing consistency. Salespeople couldn’t just walk into Sears and cut a special backroom deal. If they offered a discount, they needed a legitimate business reason, like actual cost savings from shipping in bulk, and they had to be ready to justify it.

With fair practices in play again, it also meant relationships mattered more than ever. If you couldn’t win on price, you had to win on partnership. You had to show your small and mid-sized customers that you valued them, not just the chains. In a way, Robinson-Patman democratized selling, giving every customer, big or small, a fairer shot at competing in their market.

Of course, it wasn’t perfect. Lawyers fought over what counted as ‘fair’ discounts, and over time, enforcement waned. But in the late 1930s and through the ’40s, Robinson-Patman was a clear signal: the government was stepping in to keep salespeople from playing favorites and to protect the idea of a level playing field.

Those represented the most significant of the early legislative acts that impacted the sales profession. There were certainly more, like:

The Miller-Tydings Act of 1937: This essentially was meant to stop the practice of retailers using “loss leaders” to bring people in. For example, you’re a manufacturer. You advertise. You set a price. However, you lose control once the retailer takes it and sells it. The retailer decides, “Hey, let’s advertise this product as being practically free to get people in the door, then they’ll buy other stuff.” The manufacturer became irate at this practice, because it cheapened their brand’s perceived value. They didn’t want to be a discount brand. So, the act allowed manufacturers to set a minimum price a retailer could sell a product for.

The Wheeler-Lea Act of 1938: While the FTC Act of 1914 was aimed to protect competition regarding misleading claims, Wheeler-Lea was specifically designed to protect the actual consumer. This was a big one for brands as it relates to my bias towards transparency. Bold promises that couldn’t be delivered could quickly mean your business would be gone soonafter.

The Wage Stabilization Board of 1950: This was a wild one that actually didn’t last…During World War II, inflation spiked. Along with it, wages also went up, based partially on a limit of labor due to the needs of the military – a low supply of workers equals a need to pay more for those workers. However, as wages went up, a company’s costs would go up, meaning they rose their own prices to maintain profitability.

The result? Uncapped inflation.Learning a lesson from that period, in 1950, the United States entered the Korean War. Harry S. Truman, then US President, took proactive action, and among other things, enacted something called The Wage Stabilization Board. Its task? To control wages, or in other words, to keep wages from growing in order to keep inflation from spiraling out of control.

How would this be possible without creating a mutiny? This board consisted of 18 individuals, tripartisan. Three groups of six. Group 1 – representing the public. Group 2 – representing corporate management. Group 3 – representing labor.

Why do I bring this up? Because this Wage Stabilization Board’s powers included creating regulations around sales compensation.

The “Do’s and Don’ts” on sales salaries and commissions were very specific. Since it didn’t last, I won’t go into the details, but the regulations were tight, however, the sales organizations figured out a way to get around it…

The McGuire Amendment of 1952: This one essentially reinforced Miller-Tydings by giving states the explicit authority to uphold those minimum-price laws, even if federal antitrust rules would have said otherwise. For salespeople, this meant one thing: price stability. You could walk into a customer conversation confident that the price you set wasn’t going to get blown up by a discounting retailer down the street. Margins were protected, and brand reputation was preserved. It also meant you weren’t discounting your way to deals…you had to win them over with service, availability, and relationship strength.

And one last big one…

The Consumer Goods Pricing Act of 1975

Through the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s, those fair-trade laws like Miller-Tydings and the McGuire Amendment gave manufacturers the power to set minimum resale prices. For decades, that meant salespeople had a kind of safety net. If you sold a branded product, you knew retailers couldn’t slash prices and drag you into a race to the bottom. Your job was to protect the brand, hold the line, and sell on value.

But by the late 1960s and early ’70s, consumers were complaining of feeling trapped, and critics were agreeing.

President Gerald Ford’s Approval of the Consumer Goods Pricing Act of 1975

Why should consumers be forced to pay a set price for toothpaste, or aspirin, or a washing machine, just because the manufacturer said so? Discount retailers were popping up, eager to compete on price, places like Kmart and Walmart were gaining traction, but fair-trade laws tied their hands. They couldn’t use low prices to win business even if their lower costs would allow it.

Economists piled on, too. They argued that fair-trade laws kept prices artificially high, protected inefficient businesses, and hurt consumers. Free-market ideology was on the rise, and Congress eventually agreed.

So in 1975, the Consumer Goods Pricing Act repealed both Miller-Tydings and McGuire. No more manufacturer-set minimum resale prices. Retailers could charge whatever they wanted.

For salespeople, this was a massive shift. Overnight, the price floor disappeared. Discounting wars began. If you were in sales during the late ’70s, you suddenly faced buyers who’d say, ‘I saw this cheaper down the street — what can you do for me?’

The impact?

Negotiating suddenly became an essential salesperson skill. Before, you could point to the manufacturer’s price as non-negotiable. After 1975, everything was on the table. Salespeople had to sharpen their ability to defend value, handle objections, and resist the race to the bottom.

And because retail power surged, large discount chains could flex their buying power and pass savings to consumers, making them formidable customers. Salespeople found themselves negotiating not just on price, but on volume deals, shelf placement, and promotional support.

In short, the Consumer Goods Pricing Act moved the burden from the law protecting your margins to you, the salesperson, protecting your value. The government stepped back, and competition stepped in.

Today, as I’ve argued many times, the buyer hasn’t changed. They still make decisions the same way. Technology hasn’t had the impact you think it might have, and if you don’t believe me, go back and listed to a few of the old episodes of The Sales History Podcast. The biggest evolutionary driver to the sales profession has had more to do with the rules being changed than anything else.

Before the Sherman Act, selling wasn’t really selling as much as it was control and dominance.

Every time things got out of hand, the government stepped in. You’ve seen smaller hints of this over the past 40 years through things like

The Telephone Consumer Protection Act (TCPA) of 1991: This was established to protect people from intrusive telemarketing…things like automated dialers and pre-recorded messages could only be used during certain times of the day.

Do-Not-Call Implementation Act of 2003: Established as a joint effort between the FTC (Federal Trade Commission) and FCC (Federal Communications Commission), explicity supported and funded by Congress, George W. Bush signed this one in 2003, authorizing the FTC to create the Do Not Call Registry. Violating this act can cost up to $50,000 in fines according to the FTC.

President George W. Bush signing the CAN-SPAM Act into law.

CAN SPAM ACT of 2003: When considering forced acronyms, this one probably wins. The “Controlling the Assault of Non-Solicited Pornography and Marketing” Act, also signed in 2003, set nationwide rules for commercial email. No false or misleading headers. No deceptive subject lines. Clear identification of advertisements. Physical address required. Opt-out required. It was meant to put an end to the wild west of email selling.

All of this legislation we’ve discussed today were designed to shed monopolies, eliminate bait-and-switch approaches, eliminate the practices of playing favorites with prices, and ultimately protect the consumer.

What was left? Selling is what is was meant to be – based on trust, value, and transparency.

Will there be legislation that changes things in the future? I’d bet on it. The rise of AI may require the same kind of scrutiny of the snake oil and patent medicines of the 1800s.

There’s a balance needed always – between freedom and fairness. When there’s too much freedom, the customer gets screwed. When there’s too much regulation, competition is stifled. The laws will keep changing, but the principles that always last…being honest, transparent, and always having a service eye.

(find all the endnotes listed below…)

I’m Todd Caponi, CSP®. (<– links to LinkedIn)

I’ve written three books so far, The Transparency Sale, The Transparent Sales Leader, and my soon to be released Four Levers Negotiating.

I’m a sales keynote speaker and sales trainer, focused on teaching revenue organizations how to leverage transparency and decision science to maximize their revenue capacity.

It’s what I do…teach sellers, their leaders, well…entire revenue organizations how we as human beings make decisions, then how to use that knowledge for good (not evil) in their messaging (informal and formal), sales negotiations, sales presentations, and revenue leadership.

Reach out (email to info@toddcaponi.com) – for inquiries about speaking at your event or sales kickoff, for programs to upskill your customer-facing teams and leaders, or just to nerd out on sales or sales history.

- Sign up for the newsletter, which comes out every other week.

- Sign up to get on the launch list for Four Levers Negotiating.

- Pre-Order Four Levers Negotiating right now (releases January 27th, 2026), or reach out for bulk orders (> 10)

- Sherman Antitrust Act, 26 Stat. 209 (1890). U.S. Department of Justice, Antitrust Division, “The Sherman Antitrust Act (1890),” https://www.justice.gov/atr/sherman-antitrust-act-1890.

- Clayton Antitrust Act, 38 Stat. 730 (1914). Federal Trade Commission, “The Antitrust Laws,” https://www.ftc.gov/advice-guidance/competition-guidance/antitrust-laws.

- Federal Trade Commission Act, 38 Stat. 717 (1914). Federal Trade Commission, “A Brief Overview of the Federal Trade Commission’s Investigative and Law Enforcement Authority,” https://www.ftc.gov/about-ftc/mission/history.

- Robinson-Patman Act, 49 Stat. 1526 (1936). Federal Trade Commission, “Price Discrimination: Robinson-Patman Violations,” https://www.ftc.gov/advice-guidance/competition-guidance/price-discrimination.

- Miller-Tydings Fair Trade Act, 50 Stat. 693 (1937). Congressional Research Service, Resale Price Maintenance: History and Current Status.

- Wheeler-Lea Amendments to the FTC Act, 52 Stat. 111 (1938). Federal Trade Commission, “The Wheeler-Lea Act of 1938,” https://www.ftc.gov/legal-library/browse/statutes/wheeler-lea-act.

- Executive Order 10161, “Establishing the Economic Stabilization Agency and Wage Stabilization Board,” Sept. 9, 1950. U.S. National Archives.

- McGuire Fair Trade Amendment, 66 Stat. 631 (1952).

- Consumer Goods Pricing Act, 89 Stat. 801 (1975). Congressional Research Service, Fair Trade, Resale Price Maintenance, and the Consumer Goods Pricing Act of 1975.

- Telephone Consumer Protection Act, Pub.L. 102–243 (1991). Federal Communications Commission, “Telephone Consumer Protection Act,” https://www.fcc.gov/general/telephone-consumer-protection-act-1991.

- Do-Not-Call Implementation Act, Pub.L. 108–10 (2003). Federal Trade Commission, “National Do Not Call Registry,” https://www.donotcall.gov.

- Controlling the Assault of Non-Solicited Pornography and Marketing (CAN-SPAM) Act, Pub.L. 108–187 (2003). Federal Trade Commission, “CAN-SPAM Act: A Compliance Guide for Business,” https://www.ftc.gov/business-guidance/resources/can-spam-act-compliance-guide-business.

- Federal Reserve History, “The Great Inflation and Its Aftermath,” https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/great-inflation.

- U.S. Energy Information Administration, “History of the Oil Market Crises in the 1970s.”

- “Executive Order 10161, September 9, 1950,” John Woolley and Gerhard Peters, The American Presidency Project, no date.

- Horowitz, M. (1954). Administrative Problems of the Wage Stabilization Board. ILR Review, 7(3), 390-403.

- Loftus, Joseph A. “White House Ends All Wage Control, Many Price Curbs.” New York Times. February 7, 1953.

0 Comments