How Sales Saved The Union – The First National Sales Campaign.

“If ever there should be a Salesmen’s Hall of Fame, one of the first pedestals must be reserved for Jay Cooke.” – Ads and Sales, Herbert Newton Casson, 1911

Picture of Cooke from the 1860s.

Jay Cooke. Who is that?

“There is no doubt that some of the abundant glory that has gone to Grant and Lincoln ought to have gone to this Philadelphia banker-salesman.” As one editor very fitly said: “The nation owes a debt of gratitude to Jay Cooke that it cannot discharge, for without his valuable aid the wheels of government might have been seriously entangled.”

While Lincoln and Grant put down the Rebellion during the Civil War, it was Jay Cooke, a banker, who sold the bonds and brought in the money.

“Jay Cooke was unquestionably the first to launch a national sales campaign.”

And after reading about it and doing more research, I had questions…which I’m sure you will have, too, and I’ll go through them for you…

Here’s the short story of what he did.

The Civil War began in 1861. The war obviously had and would have an incredibly high cost, and the Union was already strapped for cash. At the time, the country had no national income tax system, however, they set one up in 1862 as an emergency measure. (fyi – national income tax was originally set up to be an emergency fund for national security)

The scale that Lincoln’s war demanded required more than the traditional borrowing of money from big banks or from wealthy investors.

They turned their attention to Jay Cooke, who was a well-known Philadelphia banker with deep networks and was known to be very creative.

So, according to Casson, in 1864, Cooke was appointed by Abraham Lincoln to sell government bonds.

Here’s why we’re talking about it here…

Cooke hired ~ 4,000 agents, comprising bankers, insurance salespeople, storekeepers, and traveling salespeople. This is widely regarded as the first extensive sales army mobilized to sell goods across every state in the North. Agents were selected based on a few core traits, one of which was their local influence. Where can we most quickly connect the message to local community figures who can help share the message more broadly?

Philadelphia HQ of Jay Cooke and Company

He didn’t just hire salespeople. He created an entire broad go-to-market strategy. This included investing in advertising everywhere he could. Newspapers. Posters. Pamphlets. Persuasive editorials. He established a press bureau, which, according to Casson, was the first in the world.

(One approach that I don’t appreciate as much, but he paid journalists to write favorable stories that were essentially disguised as news articles.)

The approach wasn’t to sell an ROI. It wasn’t to sell an investment. He knew that emotions and feelings drive decisions so much more than logic. So, the messaging was patriotic storytelling. People wouldn’t just be investing, they would be supporting the Union cause, helping the soldiers, and thereby saving the republic. He inspired sales emotionally – and basically democratized investing in government bonds. In other words, instead of just selling to rich people, he transformed the sales effort into a movement among the masses. The middle class – families, farmers, and shopkeepers could invest in these lower-denomination bonds.

The bonds had names designed to convey the terms and interest…so that regular citizens could understand them. Normally, something like this would have some governmenty name…but these were named to be marketing devices.

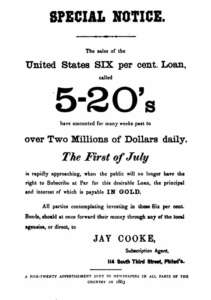

- 5-20 Bonds (the “Five-Twenties”), issued under the Loan Act of 1862, paid 6% annual interest in gold. Why the name 5-20s? Because they were redeemable after 5 years but not later than 20 years. “Safe in gold, redeemable anytime after 5 years.”

- 7-30 Bonds (the “Seven-Thirties”) were shorter-term treasury notes issued starting in 1864. They paid 7.30% annual interest (which worked out to around 2 cents a day on every $100 invested) – really easy, memorable hook for people to understand. They matured in three years. “Two cents a day for every $100 you invest.”

Cooke personally networked with community leaders in as many towns as possible, including bankers and even clergy. He inspired church leaders to preach about the importance of considering these investments.

Other bankers were shocked by his approach, with some even saying he was no financier, but “nothing but a pedler of patent medicine.” But Cooke kept going.

“Such was his energy that in a few months the North went into a fit of bond-madness.” Once complete, it was determined that Cooke’s efforts resulted in sales of $1,240,000,000. One-point-two-billion-dollars.

“Such was the result of the first national sales campaign in the United States”. Cooke’s sales campaign was responsible for nearly two-thirds of all the money raised by the Union during the war. His efforts meant armies were fed, clothed, and armed.

Picture of Cooke and his son during the 1860s Civil War

From all the reading on his story and efforts, it’s pretty clear to me that he wasn’t just a money raiser; he pioneered techniques that combined what today we would believe to be sales best practices, psychology, “social selling”, and ultimately mass persuasion. What he was selling, he turned into an emotional, patriotic, and, while maybe a stretch, moral obligation. Without this sales campaign, the Union likely wouldn’t have been able to finance the war, and what would our country look like today?

So, that’s the story…but immediately, I had to dig further into the sales elements of the story. The first question that came to mind…how do you find and train 4,000 salespeople in the 1860s? How do you onboard and ramp them? How do they get paid? And the answers I found match what the answers would likely be if we were talking about a campaign today.

Starting in Philadelphia, Cooke had established marketing materials that would be used for both advertising and enablement. Things like pamphlets, circulars, and the placing of newspaper advertisements. These elements made up some of the earliest forms of sales enablement content.

Cooke wrote letters directly to the agents in the field, which included talking points and coaching. Surviving letters show that he advised them on things like how to respond to objections.

- People felt in some cases that the war wasn’t going well, and that throwing more money was a fool’s errand. The agents were taught not to argue against that perspective. Instead, they were taught to reinforce the reward for winning the war, and how support was needed now more than ever.

- People were worried about the bonds’ backing, so the agents were taught how to make buyers feel comfortable that “the bonds are backed by the full faith of the United States.”

- The agents were also taught how to frame the urgency of the investment. There was no time to think it over. “This is your chance to stand with the Union today.”

- In the biography of Cooke in 1907, there’s an image of one of the circulars sent to the agents. It was a full Q&A answer to every question someone could conceivably ask when considering the investment.

1863 Advertisement of the 5-20s from 1863

The agents were taught how to identify and educate community leaders, including clergy, newspaper editors, and business owners…who in turn were asked to publicly endorse the purchase of bonds. It’s so much like an 1860s version of social media…

The agents were on a commission-only plan, but Cooke had selected agents whose patriotism would serve as a stronger motivator than just the money. And, Cooke was really good at reminding the agents that their role was potentially just as important as the role of the soldiers fighting on the battlefields. The agents were, according to Cooke, “financing victory”.

Agents had to sign a compensation plan…

In it, they were required to spend a “liberal portion” of their commission on popularizing the bonds through daily exertions, circulars, and ads. Not give discounts to mere investors. Enforce the same standards on any sub-agents working under them.

Want to know how the dollars worked on all of this?

First, Cooke and his firm were essentially set up as a treasury entity to sell these bonds. It’s almost as though the treasury hired them to serve as a VAR or MSP in today’s terms. Cooke’s firm had to post bonds totalling $600,000 to guarantee the fidelity of the program. That’s a huge personal risk on their behalf.

Ok, so how did Cooke’s operation get paid, and therefore the agents?

The treasury paid Cooke .375% commission on the bond value. Not 3.75%. .375% So, for every $1,000 bond sold, they would receive $3.75.

If you were an agent and brought in $100,000 of bond sales, Cooke’s agency received $375 in commission from the treasury. Then, the sub-agent (the local bankers and merchants who would actually “make the sale” and administer it) would take around ⅛% – so they would receive $125 of that $375. The traveling agents would receive a portion that wasn’t clearly defined, including reimbursement for their travel expenses. The traveling agents were more like “force multipliers” than actual closers. They would tee up the sale for the sub-agents…like traveling SDRs.

What’s also interesting is that these traveling agents, or what was often referred to as being one of Cooke’s “traveling generals,” carried status. After the war, it opened doors for them in banking, politics, and business.

So, in essence, he built a distributed sales organization, he established standardized sales and marketing materials, he built a commission plan, and he aligned messaging across 4,000 salespeople. He achieved this by utilizing scripts and messaging to handle objections, and by building an intrinsically inspired sales culture through purpose-led leadership.

Side notes:

-

I also read that Cooke overextended himself after the war in investments in railroads, and during the panic of 1873, he went bankrupt. Amazing how often these incredible salespeople end up in such dire straits, though

-

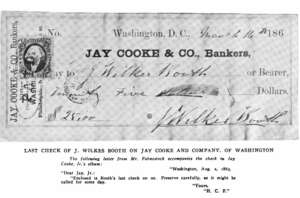

After Lee had surrendered, the 7-30 bond was still available, and still seen to be a good, safe investment. Even John Wilkes Booth bought one…not long before assassinating Abraham Lincoln. Remember that Booth came from a well-off family, and in some cases, it was seen as a good move visually to show support for the union even while you may have been staunchly opposed.

Primary Sources: Jay Cooke – Financier of the Civil War, Volume I and II, Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, PhD. 1907 and Ads and Sales, Herbert N. Casson, 1911

I’m Todd Caponi, CSP®. (<– links to LinkedIn)

I’ve written three books so far, The Transparency Sale, The Transparent Sales Leader, and my soon to be released Four Levers Negotiating.

I’m a sales keynote speaker and sales trainer, focused on teaching revenue organizations how to leverage transparency and decision science to maximize their revenue capacity.

It’s what I do…teach sellers, their leaders, well…entire revenue organizations how we as human beings make decisions, then how to use that knowledge for good (not evil) in their messaging (informal and formal), sales negotiations, sales presentations, and revenue leadership.

Reach out (email to info@toddcaponi.com) – for inquiries about speaking at your event or sales kickoff, for programs to upskill your customer-facing teams and leaders, or just to nerd out on sales or sales history.

- Sign up for the newsletter, which comes out every other week.

- Sign up to get on the launch list for Four Levers Negotiating.

- Pre-Order Four Levers Negotiating right now (releases January 27th, 2026), or reach out for bulk orders (> 10)

0 Comments